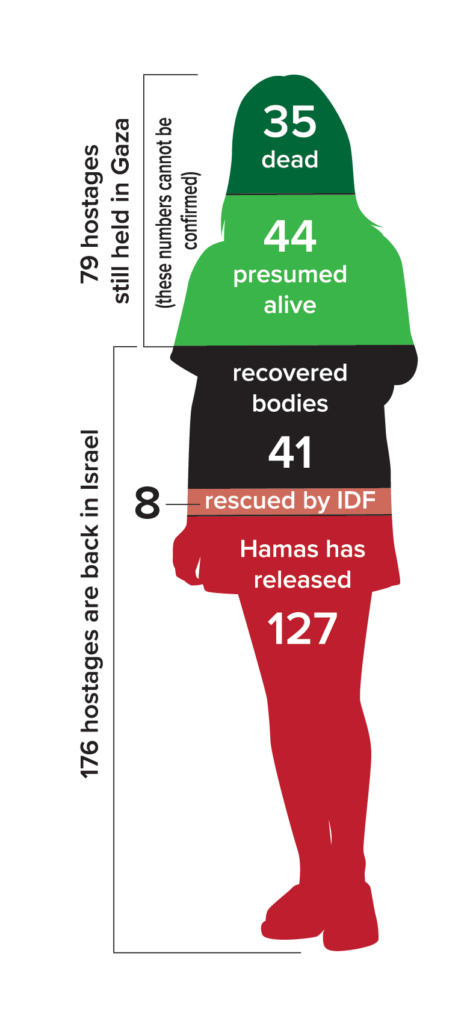

On October 7, 2023, Hamas and other Palestinian militants stormed Israel’s border, slaughtering 1,200 innocent civilians and taking 250 people hostage. A few were already released or rescued by the Israel Defense Forces. Others were set free as part of a temporary ceasefire and Palestinian prisoner exchange. Israel has a long history of ongoing attacks from its neighbors, sometimes resulting in the need to rescue or negotiate for the release of Israeli soldiers and citizens.

The rise of radical Islamic groups—Hamas, Palestinian Islamic Jihad, and Hezbollah, to name a few—has unfortunately led to Israel’s history of its enemies capturing and holding hostages. One of the first malicious events was the hijacking of an El Al flight from Rome to Tel Aviv in 1968. While some of the passengers were released within twenty-four hours, the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP) ultimately held twelve Israeli men hostage. One Jerusalem Post journalist describes the deal: “The PFLP demanded, with Algerian backing, the release of more than 1,000 prisoners by Israel. However, . . . a deal was reached in which Israel released sixteen Palestinian prisoners.” [1]

That hijacking became the predecessor of terrorist activities that would plague Israel for decades, in which a disproportionate number of Palestinian prisoners would be released in return for Israeli hostages. The PFLP struck again in 1982 by capturing three Israeli soldiers during the 1982 Lebanon War. The PFLP leader at the time was Ahmed Jibril, who negotiated a hostage exchange with Israel in which Israel released 1,150 Palestinian prisoners to get the soldiers back. Boaz Ganor, founder of Israel’s Institute for Counter-Terrorism, noted, “Following this prisoner exchange, hundreds of Palestinian terrorists, most of whom were convicted of murder and terrorist attacks, returned to live in the West Bank and Gaza Strip. This mass release of terrorists led to the establishment of the Palestinian Islamic Jihad movement.” [2]

Why would Israel engage in these unfair exchanges? The only other option would be to attempt a rescue operation. Since the kidnapping of the hostages on October 7, 2023, Israel has launched several campaigns designed to retrieve Israelis held in Gaza. However, this strategy brings with it some tough challenges. Hamas constructed hundreds of miles of underground tunnels and used schools, hospitals, and aid centers to disguise the tunnel entrances and holding areas.

These challenges came into full view on June 8, 2024, when Israel planned and carried out a rescue operation that brought four Israelis home. Despite the successful maneuvers, leaders almost pulled the plug on the rescue. The Times of Israel reported the success of this operation but also quotes the Shin Bet (one of the Israeli security agencies) director, Ronen Bar, and IDF Chief of Staff Herzi Halevi as saying, “Conditions for the rescue were not optimal at one of the two locations in which the hostages were held. This would make it more difficult to access both locations at the same moment—a critical element of the operation to prevent terror operatives from harming the hostages.” [3]

We also know that not every rescue attempt is successful. In 1994, Israeli soldier Nachshon Wachsman was kidnapped by Hamas, who demanded the release of 200 Palestinian prisoners in exchange for Wachsman. Israel made every effort to retrieve Wachsman through negotiations but ultimately felt that a military extraction was the only way to proceed. Matthew Levitt, director of The Washington Institute’s Stein Program on Counterterrorism and Intelligence, noted, “Eight minutes after the raid began, three terrorists and one commando were dead, nine commandos were injured, and two terrorists were captured.” [4] During the mission, Hamas murdered Wachsman.

The failed rescue taught an important lesson to then-Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin. Daniel Byman, professor in the School of Foreign Service at Georgetown University, wrote, “In hindsight Rabin’s approach of separating peace talks and counterterrorism was unrealistic. Part of the purpose of [the] Oslo [Accords] . . . was to end terrorist violence.” [5] From that point on, releasing abducted Israelis and peace treaty negotiations were conducted together.

In October 2000, Hezbollah abducted Elchanan Tannenbaum, an Israeli colonel, in Dubai and took him to Lebanon. Matthew Levitt remarked in his book about Hezbollah,

The parties agreed to a deal under which Israel would release some 435 prisoners . . . as well as the bodies of sixty Lebanese killed in clashes with Israeli forces, in return for Tannenbaum and the bodies of three Israeli soldiers killed during the Hezbollah operation when the kidnappings occurred. [6]

What the PFLP had learned under Jibril, Hezbollah perfected. [7] The idea of releasing large numbers of prisoners in exchange for relatively few Israelis had an exponential return on investment for the terrorists. Terrorist activities increased when those Palestinians who were released took the opportunity to expand their efforts. The Palestinians released in the Jibril agreement formed a new organization, the Palestinian Islamic Jihad. [8]

Israel’s Shin Bet’s research reveals that 45 percent of those released in prisoner exchanges return to terrorist activity.

One example is Luay Saadi. Saadi was one of the prisoners released in the Tannenbaum deal. He later established a terror network responsible for thirty Israeli deaths and injuries to more than 300 people. In 2011, the leader of the Mossad (similar to our CIA) stated that “231 Israelis were slaughtered by those freed in the Tannenbaum exchange.” [9]

Israel also released the mastermind of the October 7 massacre, Yahya Sinwar, in a deal to release Gilad Shalit, who was taken on June 25, 2006, and imprisoned by Hamas for five years. Right after Shalit was taken, Hamas negotiated the release of more than 1,000 prisoners for Shalit’s life. [10] This deal would not be consummated until October 18, 2011.

Israel’s history of hostage deals and negotiations reveals the complexities of its national security strategy. Each incident requires a delicate balance of ethical considerations, security imperatives, and diplomatic maneuvering. As the geopolitical landscape continues to evolve, Israel will undoubtedly face new challenges in its efforts to protect its citizens and navigate the perilous terrain of hostage negotiations.

Current Hostage Deal

Israel military spokesman Rear Admiral Daniel Hagari issued a statement upon the release of three of the October 7 hostages: “Alongside the great excitement, our hearts are with all the hostages who are still held in Gaza under inhumane conditions.” Hagari spoke on behalf of most Israelis at the delight and relief that three women, Emily Damari, Romi Gonen, and Doron Steinbrecher, were delivered after 471 days from the living hell to which Hamas subjected them.

We expect more hostages to be released in the days ahead. We pray!

For Israelis, this agreement was not a mere deal or a negotiation. It is much deeper and personal to the millions of Israelis who consider the release of these three women, and the others Hamas has promised to release in the future, as saving the lives of Israel’s most precious possessions: sons, daughters, husbands, and wives. The value of each of these lives is immeasurable.

For Jewish people, the cost of their release is less important than the value of their lives. The hundreds of Palestinian prisoners and terrorists being released are considered inconsequential compared to the Israeli hostages.

In Judaism, the principle of pikuach nefesh is Hebrew for saving a soul. This tenet avers that preserving human life overrides virtually any other religious rule. This time-tested Jewish value takes precedence over Israel’s concessions to Hamas.

In the past, the State of Israel has negotiated for the release of hostages—civilians and prisoners of war. The price of a Jewish person is so precious that Israel is willing to pay the price—no matter how high—for the freedom and lives of other Jewish people. In a way, Jesus acted similarly for the Jewish people (and the nations of the world). He willingly gave His life for our redemption from sin and death (Isaiah 53:5).

There are many stories about godly men and women who sacrificed their lives for the good of the Jewish people: rabbis running into burning synagogues amid persecution to save lives and Torah scrolls, taking a stand against idolatry even when it might cost a person their life. The long list of sacrificial martyrs throughout Jewish history reminds us of Hebrews chapter 11, where we are introduced to some of the great self-sacrificing heroes of the Hebrew Scriptures. Sacrifice on behalf of others is a cherished and consistent Jewish value, and we see this now, as well, in the reporting of stories about heroism during the October 7 massacre.

We pray the Jewish community will honor those who became martyrs for the faith, and ultimately, we hope that they will recognize Jesus as the chief among martyrs who gave His life for all mankind through His sacrificial death for our sins.

We must continue to pray for the release of the rest of the hostages and Israel’s ongoing diligence to withstand the increase of potential terrorists who might emerge in the years ahead.

May the Lord have mercy on His chosen people.

Endnotes

1 Simcha Pasko, “On This Day: El Al Flight 426 Hijacked by PFLP,” The Jerusalem Post | JPost.Com, July 23, 2021, https://www.jpost.com/israel-news/on-this-day-el-al-flight-426-hijacked-by-pflp-674735.

2 Boaz Ganor, Israel’s Counterterrorism Strategy: Origins to the Present, Columbia Studies in Terrorism and Irregular Warfare (New York: Columbia University Press, 2021), 90.

3 Times of Israel staff, “New Details on Hostage Rescue Indicate Operation Was Nearly Canceled at the Last Minute,” Times of Israel, June 15, 2024, https://www.timesofisrael.com/new-details-on-hostage-rescue-indicate-operation-was-nearly-canceled-at-the-last-minute/.

4 Matthew Levitt, Negotiating Under Fire: Preserving Peace Talks in the Face of Terror Attacks (Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2008), 83.

5 Daniel Byman, A High Price: The Triumphs and Failures of Israeli Counterterrorism (New York: Oxford University Press, 2011), 85.

6 Matthew Levitt, Hezbollah: The Global Footprint of Lebanon’s Party of God, 2nd edition (Washington DC: Georgetown University Press, 2015), 225.

7 Ronen Bergman, “Gilad Shalit and the Rising Price of an Israeli Life,” The New York Times, November 9, 2011, sec. Magazine, https://www.nytimes.com/2011/11/13/magazine/gilad-shalit-and-the-cost-of-an-israeli-life.html.

8 Bergman. “Gilad Shalit and the Rising Price of an Israeli Life.”

9 Charles Byblezer, “A Brief History of Palestinian Prisoners Releases,” The Jerusalem Post, April 24, 2013, sec. Opinion, https://www.jpost.com/opinion/op-ed-contributors/a-brief-history-of-palestinian-prisoners-releases-310960.

10 Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica, “Gilad Shalit,” in Encyclopedia Britannica, January 18, 2025, https://www.britannica.com/biography/Gilad-Shalit.

11 Jonathan Lis et al., “Romi, Doron and Emily: First Hostages Released in Gaza Cease-Fire Deal Return to Israel,” Haaretz, January 19, 2025, sec. Israel News, https://www.haaretz.com/israel-news/2025-01-19/ty-article/.premium/romy-doron-and-emily-first-hostages-released-in-gaza-cease-fire-deal-return-to-israel/00000194-7f72-d57c-a597-ffff07f20000.

12 George Robinson, Essential Judaism: A Complete Guide to Beliefs, Customs, and Rituals, Updated (New York: Atria Paperback, 2000), 185.

Sign up to receive our email newsletters

Get the latest news from Israel, insights from Dr. Mitch Glaser, international ministry reports, as well as videos and podcasts, downloadable resources, discounts in our online store, and much more!